Providing the opportunity for the kind of collaboration that the construction industry so badly needs….

Design-Build has a spectrum, ranging from almost as dysfunctional …. all the way to almost as collaborative as Integrated Project Delivery.

Shifting Design-Build toward IPD

This blog entry was co-authored by Oscia Wilson and Lisa Dal Gallo

We are big proponents of Design-Build because it places designers and builders in the same room, thus providing the opportunity for the kind of collaboration that the construction industry so badly needs. Opportunity for collaboration, however, is not the same as a guarantee of collaboration. Design-Build has a spectrum, ranging from almost as dysfunctional as Design-Bid-Build all the way to almost as collaborative as Integrated Project Delivery.

Figure 1: Depending on how the Design-Build structure is implemented, a project can be nearly identical to an IPD structure or very dysfunctional

On the left of this spectrum, you have those Design-Build projects that use bridging documents, lowest bidder selection, and a team that doesn’t work well together. Although the builders are contractually combined with the architect of record, these projects are not collaborative, let alone integrated.

Owners, this is bad for you. The biggest problem with this model is that when you have an architect prepare bridging documents, you’ve just made all the big decisions without the input of the building team. Since 80% of the cost decisions are made during the first 20% of the design, you’ve just cheated yourself out of the biggest source of potential savings that come from collaboration between the contractors and the designers.

On top of that, now you’ve divided your design team into two groups: the architects who did the bridging documents, and the architects who finish the project. This creates knowledge transfer loss, inefficiencies due to effort repetition, and prevents the second architect from holding a sense of ownership over the design.

In addition, if your selection is based solely on price, the Design-Build team will price exactly what is on the bridging documents; there is no incentive for the team to engage in target value design. This situation could be improved by offering an incentive through savings participation, but that kind of aggressive innovation requires a high functioning team. If the selection was based on lowest bid, the team may be too dysfunctional to achieve real gains because the lowest prices generally come from the least experienced and least savvy of the potential participants. Often in these settings, cost savings are achieved at the expense of quality design, as general contractors under great pressure to achieve aggressive cost savings revert to treating architects and engineers as venders instead of partners.

For owners who want intimate involvement in the process, Design-Build based on low bidding offers another disadvantage. In order for the Design-Build team to deliver for that low price you were so excited about, they have no choice but to ruthlessly cut you out of the process. They are carrying so much risk that they can’t afford any of the potential interference, delay, or scope escalation that comes from involving a client in the back-room discussions.

If you have a team that works well together, you move farther to the right on the spectrum.

If you hire the design-build team based on good scoping documents instead of bridging documents, you move farther to the right on the spectrum. (Partial bridging documents may be a good compromise for public owners whose process requires a bridging step.)

Starting somewhere in the middle of this spectrum, you start seeing successful projects. A successful, collaborative Design-Build project is light years ahead of Design-Bid-Build.

Some projects are pushing the envelope so far that their Design-Build projects look very similar to Integrated Project Delivery (IPD). Lisa Dal Gallo, a partner at Hanson Bridgett is an expert in IPD and partially integrated projects, including how to modify a Design-Build structure to get very close to an IPD model. She recently discussed this topic at both the San Diego and Sacramento chapters of the Design-Build Institute of America (DBIA). The discussion was mainly to assist public owners who have design-build capability to improve upon their delivery, but same principles apply to private owners who may not be in the position to engage in a fully integrated process through an IPD delivery method.

Several recent and current projects in California are operating on the far right side of this Design-Build collaboration spectrum, by crafting a custom version of Design-Build that uses IPD principles. Here’s how they’re doing it:

- Skipping the Bridging Documents. Instead of using bridging documents as the basis for bidding, owners are creating scoping criteria or partial bridging documents that provide performance and owner requirements, but allow the design team to collaborate on the design and present their own concept to achieve the owner’s goals. Under this type of scenario, the design-build teams would typically be prequalified and then no more than 3 teams would be solicited to participate in design competition.The team is usually selected based on best value. After engagement, the owner and end users work with the team through the scoping phase and set the price.

- Integrating the Design-Build entity internally.

- To assist in a change in behavior, the general contractor and major players like architect, engineers, MEP subs, and structural subs can pool a portion of their profit, proportionally, sharing in the gains or pains inflicted based on the project outcome.

- Through downstream agreements, the major team players can also agree to waive certain liabilities against each other.

- They enter into a BIM Agreement and share information freely, using BIM to facilitate target value design and a central server to allow full information transparency.

- Partially integrating with the owner. The owner can play an active role, participating in design and management meetings.

The extent to which the owner is integrated with the design/build team is a subtle—but crucial—point of differentiation between an extremely collaborative form of Design-Build (which I suggest we call “Integrated Design-Build”) and Integrated Project Delivery.

Here is the crux of the biscuit: Under an IPD model, the owner actually shares in the financial risks and rewards associated with meeting the budget and schedule[1]. Therefore, they are part of the team and get to fully participate in back-of-house discussions and see how the sausage is made.

Under Design-Build, even an Integrated version of Design-Build, the design-build entity is carrying all the financial risk for exceeding a Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP) and/or schedule, so they deserve to collect all the potential reward if they can figure out how to bring it in faster and cheaper. Since the owner’s risk for cost and schedule is substantially reduced when the project uses a GMP, the owner doesn’t really deserve a spot at the table once they’ve finished clearly communicating their design and performance criteria (which is what the scoping documents are for).

It can be an awkward thing trying to incorporate a client who wants to be involved, while making sure that client doesn’t request anything above and beyond what is strictly communicated in the scoping documents upon which the GMP is based.

So the key differences between this Integrated Design-Build and full Integrated Project Delivery are:

-

The contract model (a multi-party agreement between Owner, Architect and Contractor vs. an agreement between owner and usually the contractor)

-

The level of owner participation in the decision making process

-

The fee structure and certain waivers of liability (shared risk) between the owner and the other key project team members.

Figure 2: Traditional design-build is hierarchical in nature. An integrated design-build model is collaborative in nature (but only partially integrates with the owner). An IPD model is fully collaborative with the owner and may or may not include consultants and sub-contractors inside the circle of shared risk & reward, depending on the project.

The IPD contract form of agreement is aimed at changing behaviors, and its contractual structure exists to prompt, reward, and reinforce those behavior changes. However, full scale IPD is not right for every owner or project; it is another tool in a team’s tool box. The owner and its consultants and counsel should determine the best delivery method for the project and proceed accordingly. The important thing to remember is that any delivery model can be adapted to be closer to the ideal collaborative model by making certain critical changes. What is one thing you might change on your next project to prompt better collaboration?

[1] Under IPD, a Target Cost is set early (similar to a GMP). If costs exceed that target, it comes out of the design & construction team’s profits. But if costs go so high that the profit pool is exhausted, the owner picks up the rest of the costs. If costs are lower than the target, the owner and the team split the savings.

Lisa Dal Gallo is a Partner at Hanson Bridgett, LLP, specializing in assisting clients in determining the best project delivery method to achieve the teams’ goals, developing creative deal structures that encourage use of collaborative and integrated delivery processes and drafting contracts in business English. She is the founder of California Women in Design + Construction (“CWDC”), a member of the AIA Center for Integrated Practice and the AIA California Counsel IPD Steering Committee, and a LEED AP. Lisa can be reached at 415-995-5188 or by email at ldalgallo@hansonbridgett.com.

Oscia Wilson, AIA, MBA is the founder of Boiled Architecture. After working on complex healthcare facility projects, she became convinced that Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) was key to optimizing construction project delivery. She founded Boiled Architecture to practice forms of Integrated and highly collaborative project delivery. She serves on the AIA California Council’s committee on IPD.

Oscia Wilson, AIA, MBA is the founder of Boiled Architecture. After working on complex healthcare facility projects, she became convinced that Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) was key to optimizing construction project delivery. She founded Boiled Architecture to practice forms of Integrated and highly collaborative project delivery. She serves on the AIA California Council’s committee on IPD.

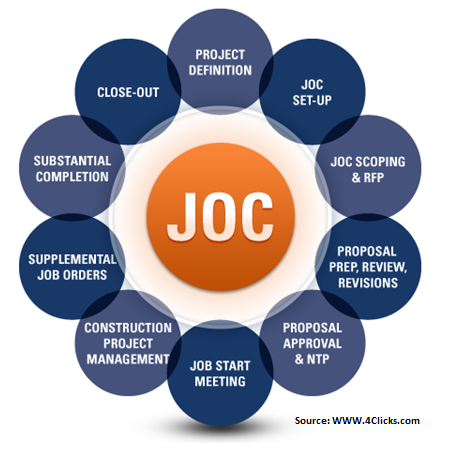

via http://www.4Clicks.com – Premier cost estimating and efficient project delivery software ( JOC, SABER, IDIQ, MATOC, SATOC, MACC, POCA, BOA… featuring an exclusively enhanced 400,000 line RSMeans Cost database with line item modifiers and full descriptions and integrated visual estimating/QTO, contract/project/document management, and world class support and training!

Job Order Contracting – JOC – is a proven form of IPD which targets renovation, repair, sustainability, and minor new construction, while IPD targets major new construction.